First, I would like to make a correction to one of the captions to my photographs from Wednesday: the image of the ship tilting and the man who seems to be holding a line that is connected to the ship- It is the 'Isabel' not the 'Sophia'. Apologies, please.

As to not having posted yesterday, I don't really want to go back so I will briefly tell about the various information I was reading. After being at the Royal Geographic Society all day (on Thursday), I now have a soft spot in my heart for the National Maritime Museum CAIRD library. As it isn't anything bad or dramatic, I don't need to go into it.

I read through the 'Report of the COmmiitee appointedy by the Lords Commission of the Admiralty to enquire into the Causes of the Outbreak of Scurvey in Recent Arctic Expeditions'. Phew! quite the title! And it was quite the document! With questioning/testimonies of many officers, medical doctors, and Captain Nares, whose ships were in question, the 'Discovery' and the 'Alert'. Now Captain Nares's expedition is also the one whose photographs are currently part of the 'Freeze Frame' exhibition at the N. Maritime Museum. The document was complete with scientific tests done on the food rations that came back from their expedition, logs of how many days the various sledge teams were out in the field compared to the number of days they were on the ship, how much they were carrying, how much they were eating (or not eating), etc. It was a lengthy read and I became quite done with it after a while. The expedition had the most cases of scurvy than any other thus far in the 1800's, yet the expedition's dates were 1875-1876! So late in the game!

It was the first time I had come across a list of medicines and tinctures they brought with them and the personal items such as bedding, shoes, for the crewmembers.

Interestingly, there is a comparison in this report of 'Dietary of Convicts at hard labour compared with the dietaries of the sailors on board ship, and of those belonging to the sledging party' by a Dr. Guy (p. 369). According to the chart, the convicts ate more (and better) and drank more than the sailors had during their arctic expedition.

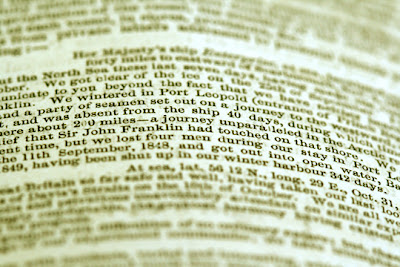

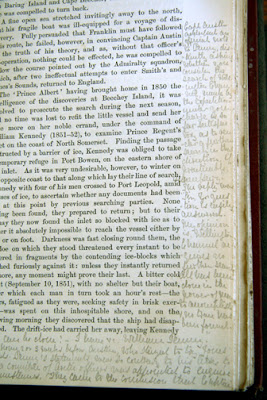

After this I moved onto 'Arctic Expedition. Further Correspondence and Proceedings connected with the Arctic Expedition' from 1852 which was both houses of parliament's record of all documents/letters/conversations they had. Again, a lengthy reading. But it was completely fascinating in that it gave provision lists for various expeditions. It also had Captain Austin's suggestions for new provisions, as I had mentioned in Wednesday's post, and the reasons behind those new requests. Such as moccasins as opposed to the leather boots they were wearing. Another list was of the items found in Aug. 26 & 27, 1850 on Beechy Island by 'Lady Franklin' and 'Sophia' crewmembers.

I left the R.G. Society feeling a bit daunted by the massive amount of information I still need to find, read, get through, perhaps digest and try to match up/make sense of. I wandered around for a bit, which didn't help, and then ended up coming back to the house and drinking a bit of wine, still quite unable to digest the concept of piles and piles of information. This, though, is one of the key reasons I am interested in the Franklin story. The massive amounts of attention Sir John and his crewmembers received and still do: The public outpouring in the mid 1800's that continues and how fact and fictions often blur and all become part of a historical 'event'. This is the brilliant aspect of 'history': it can bend and shift, over many decades and centuries until is turns into something else, something quite different. After learning 'art history' in college and then being part of that which now teachest it, (as a grad student to incoming freshman students last year), there are those things one learns and relearns at a later date only to find that everything has changed! everything has morphed! It is a theme that is so apparent in 'art history': there are 'women artists' and 'African American artists' and then there are the 'artists'. Not really. They are all 'artists', who just happen to be biologically a little different.

As I find more information from documents, I learn that what I have read from more current books have certain twists. Some say Sir John Franklin was not a very good Captain. Some say he was. Each takes its own angle, which becomes very confusing when one is trying to be earnest in their 'fact-finding-mission'. I laugh because I, too, fell into my own trap! This brings me to today's 'Freeze Frame Lecture' at the Museum. The two guest lecturers were Professor Andres Lambert from King's College speaking about how the real driving force behind Franklin's expedition was to record magnetic variations around the arctic, particularly around the magnetic pole, and Professor Klaus Dodds from University of London discussing the history of Antarctica's land claiming fate from 1908- 1959. Both very accessable and incredible lectures.

But I am going to concentrate on Professor Lambert's lecture which clarified for me how prevalent and focused the arctic expeditions really were during this time in relationship to what was going on in the rest of Europe in terms of scientific 'firsts' and scientific data/documentation/measuring. As I had hoped and presumed, there was more to this 'Northwest Passage' travail than just ego: there was scientific data to be collected, and in vast importance to the rest of western Europe in viewing the British. It wasn't just for 'Empire', it was also for 'Science', or at least while Banks was in charge (of the Royal Society). The importance of collecting mainly the magnetic measurements of such a place as the Arctic because of the magnetic North Pole, was deemed valuable not just in 'science' but in the Navy's navigational aptitude as well. In finding these measurements, the British would be able to not just have a survey of this area but be able to adeptly navigate through any type of land just by understanding how the 'magnetic pole' influences movement: 'the development of a general theory of terrestiral magnetism' as quoted by Professor Lambert, which he compared in importance to our modern day navigationing system, GPS.

Now, in thinking about what the public was like back then and in relationship to the publishing of scientific data, which would entail dauntingly dense numbers and calculations, it should be rather evident that the regular british citizen preferred the dramatic, frostbitten, tantalizing sagas that were played out in the newspapers, books, and published personal accounts. They didn't quite like the cannabalism that was found, but they did covet the role of the grieving widow and her plight to find what happened to her courageous husband.

According to Professor Lambert, when Joseph Banks died, Sir Edward Sabine took over (at the Royal Society) as the driving force behind furthering British scientific research in the arctic. Also, different than what I had read about Sir John Franklin being the last in line of the long list of Captains to be chosen, that he supposedly was the 'last pick of the litter', Lambert argued that this was not true, although he wasn't the immediate choice: Sir John Ross was, just like I had read. But: Sir John Franklin, more because of his age than his lack of expertise was at first passed over. It was because of his supreme expertise in both navigation AND magnetic science that he was finally chosen, even despite his age. He had already been on 3 previous arctic expeditions, by land and ship. He was the only man for the job, sort of to say.

Professor Lambert also claims that of course Franklin headed towards the magnetic pole, because his main intention was to collect magnetic data around that area, which could not be taken one time but rather in multiple areas. He also argued that that was why there were 14 officers on board, a quite high amount, and so many seamen. They were there to aid in the taking of scientific data collection/research. The timing of Franklin's trip was calculated so as to link up with all the other magnetic data collecting that was occuring at stations all over the world: It wasn't happenstance that the voyage left when it did.

One question (though there are many), is why didn't the search parties then go immediately to these places in the Arctic, given that that was where Franklin was intending to go? Why did it take them so long to travel down towards King William Island and instead they went into Melville Sound and other such places?

I have other questions as well: why didn't the Admiralty and other Captains further push for the public to understand the importance of such scientific discoveries? As a contemporary example, the public display of research done in space, and especially the broadcast of the Apollo moon landing: why was the British Royal Society/Admiralty not as forceful in a public display of how important this actually was in the bigger, world view at that time? The public and writers, even Charles Dickens in his 'Household Words' weekly journal, grasped onto this romanticized speculation about what occurred to the Franklin expedition and why and how and when. The Admiralty didn't end it, didn't give the grieving families the crewmembers 'death money' or certificates but rather let it play out? Was this because it was a time of peace? But then the Crimean war occurred and the Navy (and finances) were needed again. Was it then that the Admiralty signed the death certificates? I need to dig more and see if these dates/things collide.

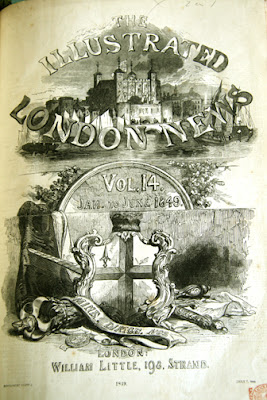

My interests lay in how the visual melodrama was played out for the public, how through visual evidence (mostly imaginary drawings done by the illustrators who they themselves had not traveled into the Arctic), the 'Arctic Unknown' was first created and through this, it was able to be then 'discovered' by these public 'heroic' polar Captains: that is was a fantastic publicity stunt pushed to the edge when you include Lady Jane Franklin as a central figure. The manner of language used in describing the captains, officers, and crewmembers far surpassed a normal image. For example, they published the accrued pages printed in the arctic of the 'Aurora Borealis', newspaper created aboard Captain Austin's ship in 1852. (This is the document I am currently going through.) It was almost mandatory that the public display their reverence towards these men who risked themselves. A disappearance, and then a re-appearance through artifacts, language, and the force of the media.

To make a contemporary comparison, how are we force fed all the same type of visual evidence to assist us in creating the 'correct' view we should have towards Iraq and our soldiers, more so at the beginning of the war than now. Supposedly, America has ventured into Iraq to save its people from the terrible leader, hidden terrorists (now quite unhidden), and from the apparent (but really quite unapparent) WMDs. America is there to prosper the people and give them 'democracy'. In thinking about publicity stunts throughout the centuries, could we just add this to the collection? The resources in that area, especially while trying to feed americans' personal vehicle lust, are far too obvious a choice when creating a bigger picture of what is really going on. To admit, I realize that I have over-simplified a grave and dark matter. It is only to get worse.

But like all governments who indeed acknowledge their first class power, America is no different, especially in the history of empires (and dictators).

It is rather frightening. 'Iraq' is an 'unknown': is 'it', whatever 'it' is today, to be feared? I have never been there and I don't think I closely know anyone who has. But thankfully, in a place like America, if you truly want to know something and find out what something is like, the internet is just a public library stop away. Blogs, soldiers' digital cameras, personal account websites and public posts, and emails have not only placed personal experience above a government stated address but it has at times undermined what the government is (trying) to proclaim.

Phew!

All this from a little research grant funded through a huge university, which is probably assisting in the war in some way. Many departments do get funding through the government since it is the bigger company always willing to give money for un/masked war research. Franklin's expedition was one of the finest funded trips thus far as of 1845. His provisions were in excess, his scientific instruments none too weak or sparse. His crew definitely were in the numbers. And two ships, to say the least. Yes, this expedition was not to fail in all that it endeavored. Yet, it did. And it left no written message as to why. It has taken countless writers, passing time, and a plethora of falsehoods to create the portrait that we, as a public, know, that yes, Franklin was triumphant, his widow grievous, and his crewmembers valiant in their disappearance: The triumph in failing! Even with the cannabalism.

As to not having posted yesterday, I don't really want to go back so I will briefly tell about the various information I was reading. After being at the Royal Geographic Society all day (on Thursday), I now have a soft spot in my heart for the National Maritime Museum CAIRD library. As it isn't anything bad or dramatic, I don't need to go into it.

I read through the 'Report of the COmmiitee appointedy by the Lords Commission of the Admiralty to enquire into the Causes of the Outbreak of Scurvey in Recent Arctic Expeditions'. Phew! quite the title! And it was quite the document! With questioning/testimonies of many officers, medical doctors, and Captain Nares, whose ships were in question, the 'Discovery' and the 'Alert'. Now Captain Nares's expedition is also the one whose photographs are currently part of the 'Freeze Frame' exhibition at the N. Maritime Museum. The document was complete with scientific tests done on the food rations that came back from their expedition, logs of how many days the various sledge teams were out in the field compared to the number of days they were on the ship, how much they were carrying, how much they were eating (or not eating), etc. It was a lengthy read and I became quite done with it after a while. The expedition had the most cases of scurvy than any other thus far in the 1800's, yet the expedition's dates were 1875-1876! So late in the game!

It was the first time I had come across a list of medicines and tinctures they brought with them and the personal items such as bedding, shoes, for the crewmembers.

Interestingly, there is a comparison in this report of 'Dietary of Convicts at hard labour compared with the dietaries of the sailors on board ship, and of those belonging to the sledging party' by a Dr. Guy (p. 369). According to the chart, the convicts ate more (and better) and drank more than the sailors had during their arctic expedition.

After this I moved onto 'Arctic Expedition. Further Correspondence and Proceedings connected with the Arctic Expedition' from 1852 which was both houses of parliament's record of all documents/letters/conversations they had. Again, a lengthy reading. But it was completely fascinating in that it gave provision lists for various expeditions. It also had Captain Austin's suggestions for new provisions, as I had mentioned in Wednesday's post, and the reasons behind those new requests. Such as moccasins as opposed to the leather boots they were wearing. Another list was of the items found in Aug. 26 & 27, 1850 on Beechy Island by 'Lady Franklin' and 'Sophia' crewmembers.

I left the R.G. Society feeling a bit daunted by the massive amount of information I still need to find, read, get through, perhaps digest and try to match up/make sense of. I wandered around for a bit, which didn't help, and then ended up coming back to the house and drinking a bit of wine, still quite unable to digest the concept of piles and piles of information. This, though, is one of the key reasons I am interested in the Franklin story. The massive amounts of attention Sir John and his crewmembers received and still do: The public outpouring in the mid 1800's that continues and how fact and fictions often blur and all become part of a historical 'event'. This is the brilliant aspect of 'history': it can bend and shift, over many decades and centuries until is turns into something else, something quite different. After learning 'art history' in college and then being part of that which now teachest it, (as a grad student to incoming freshman students last year), there are those things one learns and relearns at a later date only to find that everything has changed! everything has morphed! It is a theme that is so apparent in 'art history': there are 'women artists' and 'African American artists' and then there are the 'artists'. Not really. They are all 'artists', who just happen to be biologically a little different.

As I find more information from documents, I learn that what I have read from more current books have certain twists. Some say Sir John Franklin was not a very good Captain. Some say he was. Each takes its own angle, which becomes very confusing when one is trying to be earnest in their 'fact-finding-mission'. I laugh because I, too, fell into my own trap! This brings me to today's 'Freeze Frame Lecture' at the Museum. The two guest lecturers were Professor Andres Lambert from King's College speaking about how the real driving force behind Franklin's expedition was to record magnetic variations around the arctic, particularly around the magnetic pole, and Professor Klaus Dodds from University of London discussing the history of Antarctica's land claiming fate from 1908- 1959. Both very accessable and incredible lectures.

But I am going to concentrate on Professor Lambert's lecture which clarified for me how prevalent and focused the arctic expeditions really were during this time in relationship to what was going on in the rest of Europe in terms of scientific 'firsts' and scientific data/documentation/measuring. As I had hoped and presumed, there was more to this 'Northwest Passage' travail than just ego: there was scientific data to be collected, and in vast importance to the rest of western Europe in viewing the British. It wasn't just for 'Empire', it was also for 'Science', or at least while Banks was in charge (of the Royal Society). The importance of collecting mainly the magnetic measurements of such a place as the Arctic because of the magnetic North Pole, was deemed valuable not just in 'science' but in the Navy's navigational aptitude as well. In finding these measurements, the British would be able to not just have a survey of this area but be able to adeptly navigate through any type of land just by understanding how the 'magnetic pole' influences movement: 'the development of a general theory of terrestiral magnetism' as quoted by Professor Lambert, which he compared in importance to our modern day navigationing system, GPS.

Now, in thinking about what the public was like back then and in relationship to the publishing of scientific data, which would entail dauntingly dense numbers and calculations, it should be rather evident that the regular british citizen preferred the dramatic, frostbitten, tantalizing sagas that were played out in the newspapers, books, and published personal accounts. They didn't quite like the cannabalism that was found, but they did covet the role of the grieving widow and her plight to find what happened to her courageous husband.

According to Professor Lambert, when Joseph Banks died, Sir Edward Sabine took over (at the Royal Society) as the driving force behind furthering British scientific research in the arctic. Also, different than what I had read about Sir John Franklin being the last in line of the long list of Captains to be chosen, that he supposedly was the 'last pick of the litter', Lambert argued that this was not true, although he wasn't the immediate choice: Sir John Ross was, just like I had read. But: Sir John Franklin, more because of his age than his lack of expertise was at first passed over. It was because of his supreme expertise in both navigation AND magnetic science that he was finally chosen, even despite his age. He had already been on 3 previous arctic expeditions, by land and ship. He was the only man for the job, sort of to say.

Professor Lambert also claims that of course Franklin headed towards the magnetic pole, because his main intention was to collect magnetic data around that area, which could not be taken one time but rather in multiple areas. He also argued that that was why there were 14 officers on board, a quite high amount, and so many seamen. They were there to aid in the taking of scientific data collection/research. The timing of Franklin's trip was calculated so as to link up with all the other magnetic data collecting that was occuring at stations all over the world: It wasn't happenstance that the voyage left when it did.

One question (though there are many), is why didn't the search parties then go immediately to these places in the Arctic, given that that was where Franklin was intending to go? Why did it take them so long to travel down towards King William Island and instead they went into Melville Sound and other such places?

I have other questions as well: why didn't the Admiralty and other Captains further push for the public to understand the importance of such scientific discoveries? As a contemporary example, the public display of research done in space, and especially the broadcast of the Apollo moon landing: why was the British Royal Society/Admiralty not as forceful in a public display of how important this actually was in the bigger, world view at that time? The public and writers, even Charles Dickens in his 'Household Words' weekly journal, grasped onto this romanticized speculation about what occurred to the Franklin expedition and why and how and when. The Admiralty didn't end it, didn't give the grieving families the crewmembers 'death money' or certificates but rather let it play out? Was this because it was a time of peace? But then the Crimean war occurred and the Navy (and finances) were needed again. Was it then that the Admiralty signed the death certificates? I need to dig more and see if these dates/things collide.

My interests lay in how the visual melodrama was played out for the public, how through visual evidence (mostly imaginary drawings done by the illustrators who they themselves had not traveled into the Arctic), the 'Arctic Unknown' was first created and through this, it was able to be then 'discovered' by these public 'heroic' polar Captains: that is was a fantastic publicity stunt pushed to the edge when you include Lady Jane Franklin as a central figure. The manner of language used in describing the captains, officers, and crewmembers far surpassed a normal image. For example, they published the accrued pages printed in the arctic of the 'Aurora Borealis', newspaper created aboard Captain Austin's ship in 1852. (This is the document I am currently going through.) It was almost mandatory that the public display their reverence towards these men who risked themselves. A disappearance, and then a re-appearance through artifacts, language, and the force of the media.

To make a contemporary comparison, how are we force fed all the same type of visual evidence to assist us in creating the 'correct' view we should have towards Iraq and our soldiers, more so at the beginning of the war than now. Supposedly, America has ventured into Iraq to save its people from the terrible leader, hidden terrorists (now quite unhidden), and from the apparent (but really quite unapparent) WMDs. America is there to prosper the people and give them 'democracy'. In thinking about publicity stunts throughout the centuries, could we just add this to the collection? The resources in that area, especially while trying to feed americans' personal vehicle lust, are far too obvious a choice when creating a bigger picture of what is really going on. To admit, I realize that I have over-simplified a grave and dark matter. It is only to get worse.

But like all governments who indeed acknowledge their first class power, America is no different, especially in the history of empires (and dictators).

It is rather frightening. 'Iraq' is an 'unknown': is 'it', whatever 'it' is today, to be feared? I have never been there and I don't think I closely know anyone who has. But thankfully, in a place like America, if you truly want to know something and find out what something is like, the internet is just a public library stop away. Blogs, soldiers' digital cameras, personal account websites and public posts, and emails have not only placed personal experience above a government stated address but it has at times undermined what the government is (trying) to proclaim.

Phew!

All this from a little research grant funded through a huge university, which is probably assisting in the war in some way. Many departments do get funding through the government since it is the bigger company always willing to give money for un/masked war research. Franklin's expedition was one of the finest funded trips thus far as of 1845. His provisions were in excess, his scientific instruments none too weak or sparse. His crew definitely were in the numbers. And two ships, to say the least. Yes, this expedition was not to fail in all that it endeavored. Yet, it did. And it left no written message as to why. It has taken countless writers, passing time, and a plethora of falsehoods to create the portrait that we, as a public, know, that yes, Franklin was triumphant, his widow grievous, and his crewmembers valiant in their disappearance: The triumph in failing! Even with the cannabalism.